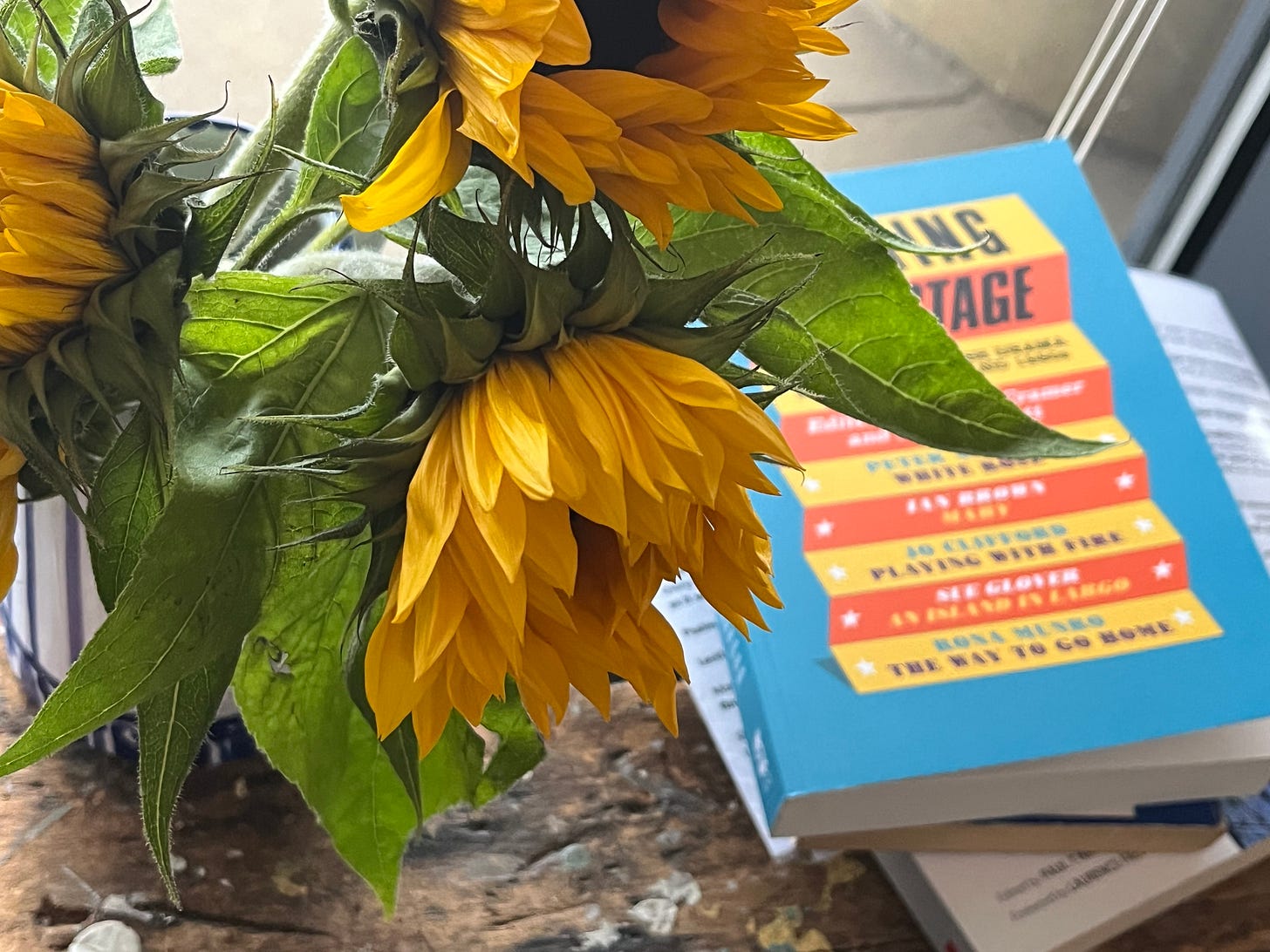

A parcel of plays

So there I was.

Sitting, looking out at the rain..

And the postie knocked on the door. He was trying to deliver a parcel that couldn’t fit through the letterbox.

When I opened it up I saw it was a book of plays.

Good plays, Scottish plays.

Plays for a country to be proud of.

Plays that in a country with a functioning theatre industry would not have been forgotten.

I don’t imagine you’ll recognise the names, but I’ll give them to you anyway:

“White Rose” by Peter Arnott.

“Mary” by Ian Brown.

“An Island in Largo” by Sue Glover.

“The Way to Go Home” by Rona Munro

and

“Playing with Fire” by Jo Clifford.

I don’t quite know how to go about communicating what this moment means to me because I’m recovering from Covid and my Covid brain finds it hard to pursue a thread.

It sort of wanders off into nowhere instead.

Yesterday a kind friend brought me coffee and sunflowers and chocolate and I was trying to draw the sunflowers when the postie came.

I was trying to draw the flowers to escape from Storm Amy and a dreary afternoon.

An afternoon imprisoned by Covid and imprisoned by the rain.

And frightened by the sense of living under the rule of a mad president.

A time of terrible cruelty and unparalleled destructiveness.

A society self-destructively obsessed with the pursuit of wealth.

And then I opened my play because I wrote it a long time ago in 1987 and I’d forgotten what it was like…

And discovered it was set in the time of a mad king.

A time of terrible cruelty and unparalleled destructiveness.

In a society obsessively and self-destructively preoccupied with the pursuit of wealth…

The main character, Justina, is an idealist who is in despair at the state of the world and wants to find a way to make it better.

She sells her soul to the devil when the devil promises he will give herthe power to do so.

But she is cruelly deceived.

The world she lives in, the world we live in, is a dark and terrible place.

Even the Devil is disgusted by it:

“People give me many names. Prince of Evil. Lord of Darkness. Its origin and source. They know nothing.

If it were true this earth would be my home. I’d be a citizen of the world. Close kin to you. I’d be the marrow of your bones. A citizen of France. With all you other citizens. Living in this grubby little city. This scabby dunghill. Huddled on the banks of a muddy little river, filthy and polluted with your dirt, on the far northern fringes of the civilised world.

You clutch your pitiful rags to cover your nakedness and build your wretched little hovels of stone. Your god is an instrument of torture that night and day you meditate upon to devise new means of tormenting each other. Your people are starving. In every alley, every street, every square and every hedgerow you can hear the cries of your hungry children. And they could be fed. They could be. But you choose otherwise.

Life lies all around you, Nature would welcome you with open arms, if you would but let her.

But you choose death. And you honour most of all those butchers most adept at lies, those whose only art is to perfect the instruments of war.

And your king sits in his tower and he sees it all. But thinks instead of the cut of his robe. And your constable looks nowhere but over her shoulder at the rivals she fears will attack her. She fortifies her castle. She sharpens her sword. And you call me the Prince of Darkness. What gall. What pitiful presumption. Where is the darkness? Not in me.

It is in yourselves.”

One of the many uncanny things about the play is the way in which I seem to have foreseen the economics of the world we live in now.:

“The rich don’t work. Not nowadays. No-one makes money by working. They make money from having money. They get richer for being rich already. The rich sit on high balconies and look down on the tumult below. They watch the porters coming from the market, staggering to and fro under heavy loads, and they say: the poor are poor because they don’t know how to work.”

Fernando, Justina’s husband, hates poverty and wants wants to be one of the rich:

“We’ll do the same. We’ll stay in bed all day. We’ll sip exotic drinks from crystal glasses and we’ll throw a coin down from time to time. The life of the intellect.

That’s the life for me. I’ll become a philosopher. Or perhaps an economist.”

The play’s showing its age there.

Nowadays he’d say:

“I’ll run a think tank. Or go into asset management.”

Soon after Fernando is run over by a dung cart. He has a vision of his broken body in the street:

“I was walking. I was frightened. There was something I was frightened of losing. That’s all I was thinking. I didn’t want to lose it, and now it’s gone. There was a crowd. I could see a crowd. Everyone was shouting. There was this...thing, this broken thing in the middle of it all, and when I got closer I saw it was a body. A broken body. And I thought: some poor sod’s had it, anyway. And then I got closer. And I saw it was me.”

I remember years and years later being ill in a hospital ward, looking at a whole bank of heart monitors and seeing one heart beating far more irregularly and far more quickly than the rest, and thinking:

“That poor sod’s really ill.”

And then finding it was me.

Justina brings Fernando back from the dead because she loves him.

These days I dream of my late partner, Susie.

Because I still love her, I bring her back to life in my subconscious mind

The devil thinks resurrection is something not to be recommended:

“I had a client once. I took him way up a mountain. Showed him all the kingdoms of the world. He turned them down. Did him no good.

Once my client lost his friend. He wept. And then he said: he is not dead. He is sleeping. And the mourners laughed him to scorn. But he took no notice. He went and he stood before the grave and shouted. “Lazarus. Come forth!”. And Lazarus came. He had been in the grave three days. He stank. Imagine it. And the tales he had to tell are enough to freeze the blood.”

Fernando does come back to life.

And he understands:

“I was married to an alchemist.

We quarrelled all the time. The energy we spent. All the trouble we took to be unhappy. The wasted time. And the garden is still there.

Still there inside our minds. It was never lost. We thought it was. But we walk there, hand in hand. And we are not ashamed.

Why didn’t we know?

Why didn’t we understand?

Why did we fight?

Why did we hurt each other?

And I loved you. I loved you all the time.”

These words still break my heart.

And Fernando chooses death.

They all do.

All the characters choose death, just as we as a society seem to be choosing death.

All of them go out through death’s door.

Except for Justina.

“THE DEVIL HAS PUT OUT ALL THE CANDLES BUT ONE. HE GIVES IT TO JUSTINA. HE EXITS THROUGH DEATH’S DOOR. JUSTINA STARES AT HER LIGHT A WHILE.

JUSTINA

How frail a light. How easy to put out. I could do it with my hand.

They say to some death comes so sweetly, like a friend. But not to me.

The night is always darkest in the hour before the daylight comes.

Then, they say, the sun will rise and chase away the spirits of the dark.

But, till that hour we have to grope our way through shadows and await the dawn.

JUSTINA LEAVES HER CANDLE AND WALKS TO THE DOOR THAT LEADS TO THE OUTSIDE WORLD. SHE OPENS IT. DAWN IS BREAKING. WE HEAR THE SINGING OF THE BIRDS.

THE PLAY ENDS.”

Just like me, she, obstinately and perhaps inexplicably, chooses to live….

“Setting the Stage: New Wave Scottish Drama from the 1970s and 1980s”, edited by Steven Cramer and John Corbett, is published by the Association for Scottish Literature, Glasgow 2025.