Making theatre for the world

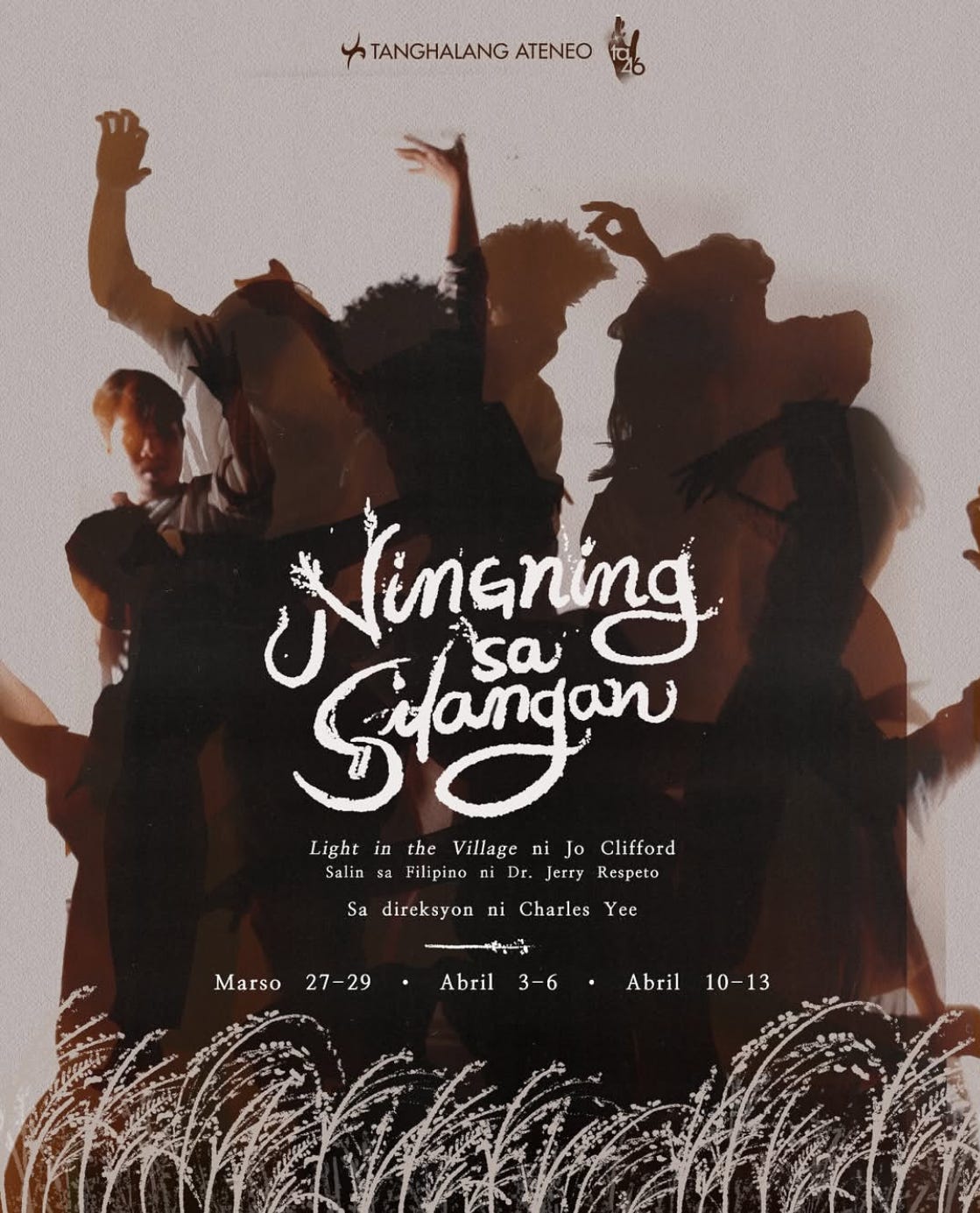

As I think about what happened while I watched the performances of “Ningning sa Silangan” -the Tagalog version of my “Light In The Village” - I find myself taken back to a different world.

The very different world of 1990-1, when I wrote the play.

I was 40 years old; and living with my partner Susan and our daughters Rebecca and Katie.

I could still freely walk and run, was able-bodied and assumed I would always remain so.

I was still living as a man and assumed I would always have to.

Suffering as a consequence.

Looking back on us as a family, we all did.

For the transphobia that so afflicted me so deeply hurt Susie too, and my daughters also.

But we all loved each other deeply and worked with all our power and strength to be happy.

And to live in the firm belief that the personal is political; and that we needed to do all we could to live as if the feminist revolution we all longed for had already happened.

And there was no internet.

So yes, it was a profoundly different world.

Even computers were pretty new back then.

I wrote my first players on a typewriter. By 1990 I was using a Word processor.

An Amstrad.

I wrote the play as I always did. As I still do:

I imagine myself as the characters, and, as best I can, feel their emotions, think their thoughts, live their lives, and hear their words.

Which I write down as best I can, for as long as I can, until I get stuck.

And then I begin all over again.

Writing “Light In The Village” I got stuck very frequently.

And then I would begin again and again. And again.

Again from the very beginning, living through everything all over again, hoping I would get further this time.

And I would give each new draft a new number.

Until eventually, I got up to 37 and the script was finished.

Until rehearsals started, and the drafting and redrafting continued.

It all took a long time and cost me much suffering.

Partly because the characters in the play all suffer, and suffer very deeply, and I suffered along with them.

But mainly because these people all lived in an Indian village and what did I really know about their lives?

And what right had I to even attempt to write about them?

And then there was Kali.

I really had no idea what the Hindu Goddess of Death and Regeneration was doing in my script.

But there She was. And I knew She had to be there.

But I could not integrate Her into the human world of the rest of the play.

It took me a very long time to discover that She needed to create the world; and that was how the play’s action should begin.

And it's only now, 30 years later, that I begin to understand how deeply that matters.

(But that's another story…)

Looking back, I can see that then I was pretty ignorant in many ways.

What I did have was a burning rage at the injustice of the world, and a burning desire to make audiences aware of it.

I also had a sense that the present order of things was coming to an end.

Humanity needed to discover a new way of doing politics, a new way of understanding economics, that would bring us in line with the total interconnectedness of our world. And still does.

Everything needed to change, including the way I wrote plays.

I wanted to create a theatre that would give pleasure in every dimension: through words, music, movement, set and lighting.

That would involve the intellect and the emotions and all the senses and dimensions.

Including the spiritual.

I was arrogant enough not to notice that all that had been tried before, almost certainly by artists who were far more gifted than myself.

But there was something else. I wanted to create theatre that was not about individuals in conflict with the world and with each other:

But that was concerned with expressing our collective experience as human beings in a world in which everything and everyone connects with each other.

That would be global in its scope. That would be a theatre of the world.

Because then, as now, we need to abandon seeing the world as a place of conflicting individual and national interests and instead move towards an understanding of the fact that we all have a mutual interest in the world and in each other.

Because that is how we will resolve our current crisis.

But the drama we are used to, the drama we revere, is essentially about individuals in conflict with each other and the world: a drama played out behind the fourth wall of the theatre.

But that theatrical form did not serve me.

But what form could?

In my previous play, “Ines de Castro”, I had had the cast double up as both individual characters and as members of the chorus.

I hadn't really meant to do this, but I’d had to, because the Traverse couldn't afford all the actors.

In "Light In The Village" that is taken a stage further.

“The story begins….”

Is the first line of the play, spoken by Actor One who becomes Mukherjee.

This was more revolutionary than I knew at the time, I suppose, because the first actor cast in the role refused to say the line.

He’s a fine actor; but to say it went against all his instincts and his training.

I refused to cut the line, and all the other storytelling lines, and he left the production .

Which was a real shame, because I admired him…

But deep down I knew I was right, though without really understanding why.

Watching Tanghalang Ateneo’s production, I am beginning to understand why.

But how to explain it?

Kali tells stories all the time.

In the other productions that I’ve seen, the actress playing her would tell the stories as a solo performance.

Always beautifully…

As she tells the story of the world’s creation, the story of the Tower of Babel, the story of Noah’s Ark, and the story of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah.

And she reminds us that we all have a right to a state of sexual innocence.

The right to inhabit a dimension of life in which we enjoy sexual pleasure without guilt or shame.

And at that moment all the actors become Kali.

What I love about Charles Yee’s production with Tanghalang Ateneo is that this idea is extended to the other stories Kali tells.

The whole company are involved in telling the stories of the Goddess.

Telling Her story with their bodies, with the most wonderful inventiveness and skill.

So they all become Mother Kali; and in doing so they transcend their individual dilemmas and tragedies and represent the whole of humanity.

We, too, living our everyday lives in this dimension also inhabit a dimension that transcends our daily concerns and connects us with the whole world.

A dimension that is most immediately accessible to us through dreams…

I hadn't really been completely aware that that's what I intended; and I'm so grateful to Charles off Yee for somehow understanding my intentions, and for the cast who so brilliantly and powerfully and courageously embody them.

The last time I saw my work performed with such beautiful physicality was way back in my 1988 “Great Expectations”, directed by Ian Brown, choreographed by Gregory Nash, and produced first by TAG Theatre Company and then by the Traverse.

And with Alan Cumming as Pip…

It was a hugely successful production; but I didn’t dare even to attempt to create another play like it, because it involved a cast of actors and dancers and needed double the usual amount of rehearsal time.

But what a shame, I think, what a shame I think now that I couldn’t develop that form further…

And then I remember something I’d totally forgotten:

That when I wrote my second play, “Lucy's Play”, back in 1986 the first stage direction read:

THE ACTORS GREET THE AUDIENCE.

And the actors then were very reluctant to do that. It made them feel so very exposed, and I felt I done something very stupid in asking them to do it.

So it made me cry with happiness to see how at the beginning of Tanghalang Ateneo’s production first the musicians, and then the actors, entered at the back of the auditorium and made their way through the audience greeting friends and acquaintances and perfect strangers as they made their way to the stage.

It was so exactly what I wanted, but I've been afraid to ask for,

And it made for the most beautiful moment…

And then something so incredibly beautiful happened at the very end.

In the play, a landless couple lay claim to a patch of land which is theirs by right.

In doing so, they are defying the landlord as his brother, who punished them by brutally beating the man and raping the woman.

Kali comforts the woman with words that made the audience in Karachi applaud so hard they brought the performance to a stop.

Words uncannily echoed by Gisèle Pelicot; addressing her qbusersM

“Sita you cannot see me

Sita you cannot hear me

You cannot feel or touch me

You’re lost in a cold dark place where comfort never comes.

But I am with you. And my heart bleeds. It bleeds for you.

Listen, Sita. Listen in the dark.

Don’t listen to the men, Sita. Listen to me.

They want you to think that every part is full of dirt. Their dirt.

That there’s nowhere they have not defiled or soiled.

They’re wrong. They’re very wrong.

They want you to feel guilty. That you’re to blame.

That you deserve no better. Don’t believe them, Sita.

Don’t believe them for a moment.

Don’t believe them when they tell you that you had it coming

That you asked for it

That its all that you deserve.

Listen. Don’t be ashamed. You’ve no cause to be ashamed.

It wasn’t you who did it. It was them. They’re the ones.

They’re the ones who did it. They’re the ones to be ashamed.

So Mother Kali comforts her and gives her the courage to castrate and kill her rapist, and then, after Kali has killed his brother, something happens that I wanted to leave the audience with a sense of empowerment, something I wanted to plant the seed that would enable them to believe that things can change, that there is another way:

FOUR

She walked out to the field.

Where her husband was staring at the wasted land.

The tiny barren patch of ground.

The dew was wet in the grass. Mist was rising from the river.

It was the hour of dawn.

SITA

Muntu. Don’t tell me what I should have done.

Don’t tell me that I should forgive.

Look at the earth Muntu. The wasted earth.

The garden that we dreamed of

Has turned into a barren patch of weeds.

Muntu we’ll dig the ground. We’ll clear it and we’ll plant our seeds.

They’ll tell us it’s a waste of time.

That others will come to take away our land.

Or else they’ll come to imprison me.

Some seeds will fall on stony ground.

Others will be eaten by the birds.

And some will be choked and smothered by the weeds

But I won’t believe they’ll all be lost

Or that our labour will be wasted.

This moment is the only thing we’ve got.

There’s nothing else.

We’ll dig. We’ll dig! We’ll dig!

end of play

In Yee’s production, the play begins with the actors reverently touching Mother Earth; throughout the performance, the cast have communicated an obvious affection for each other; and then, as the play ends Kali performs a miracle:

the dead come alive, water flows over the parched earth, there is a profound sense of joyful release

As if the words of Queen Jesus have come true:

“For we shall come to know

We are all one people in the end.”